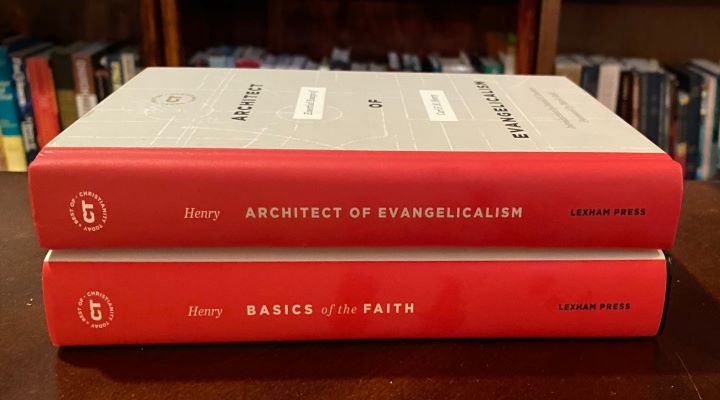

Henry, Carl F.H., Architect of Evangelicalism: Essential Essays of Carl F.H. Henry. Bellingham: Lexham Press, 2019. 480 pp. $23.99.

Henry, Carl F.H., Basics of the Faith: an Evangelical Introduction to Christian Doctrine. ed. Carl F.H. Henry. Bellingham: Lexham Press, 2019. 440 pp. $29.99.

Biographical Sketch of the Author

Carl F.H. Henry (19130-2003) was one of the most well-regarded evangelical theologians of the 20th Century. He was arguably one of the last great public intellectuals. He earned degrees from Wheaton College, Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, and Boston University. He helped start the National Association of Evangelicals in 1942. He partnered with Billy Graham in establishing Christianity Today (yes, that Christianity Today), in 1956. His magnum opus, God, Revelation, and Authority is one of the most influential evangelical works of the last 100 years.

Introduction

In this article, I have the privilege of reviewing a pair of books from the good folks at Lexham Press which function as an unofficial two-volume set by Carl F.H. Henry. He wrote in a time when “evangelical” was an identity marker that was being hotly debated. Protestants were still feeling the aftermath of the theological conflict between so-called “Modernists” and “Fundamentalists.” “Modernists” were viewed with suspicion as academic, anti-supernaturalist, closet liberals. In turn, “Fundamentalists” were cast as backward thinking, anti-science, legalists. It was in this context that Carl F.H. Henry found himself navigating. Henry argued that the wider “evangelical church” had compromised on orthodoxy in the hopes of avoiding the dreaded label of “fundamentalist.”

“Architect of Evangelicalism”

In Architect of Evangelicalism, Lexham has given us 32 of Carl F.H. Henry’s essays, spanning from 1956 to1989. The question of what it means to be an evangelical remains the central focus. In his chapter, “Evangelicals: Out of the Closet But Going Nowhere?”, the author writes “Some young evangelicals, critical of secular capitalism or of mounting militarism, have been alienated by a swift branding of their views as communist or socialist (73).” He saw a real danger of “dividing into conflicting camps prone to question each other’s biblical adequacy or even authenticity (73-74).” If those comments sound like they were made this year, you should know that Henry made them in 1980!

Henry partnered with Billy Graham and while he recognized much of the good that came out of Graham’s evangelistic crusades, he was not afraid to critique him. One of the destructive trends that Henry saw within evangelicalism was the “loss of follow up” with the thousands who came forward to profess faith in Christ at Graham’s events (78). While rightly celebrating evangelistic efforts overall, Henry had concerns about approaches that leave professed converts dying on the vine. One of the corrective steps Henry saw was fostering stewardship as “voluntary sacrifice (without legalism) in the use of resources (85-86).” As he put it, “The real test of spiritual commitment is in voluntary obedience to Christ rather than in obligation or necessity in altering one’s lifestyle (86)”.

In another essay from 1980, “Evangelicals Jump on the Political Bandwagon”, the author traces the complicated relationship between religion and politics in the United States (348-357). At the time there had been vocal groups of “Clergy for Carter” and “Clergy for Reagan (349).” Henry recognized some legitimate intentions for believers to engage with the political world, but also saw the pitfalls of triumphalism. As he put it, “The notion that a born again president will solve all the nation’s problems has run upon hard times since Jimmy Carter has occupied the White House (350).” We are reminded that 1976 had been declared “the year of the evangelical” by Time Magazine (351). Henry expressed concern that rallies like “Washington for Jesus” may have attracted huge crowds, but cost around $1 million which was money that could have been spent more wisely and effectively in his estimation (352).

In an appropriately biting address to the 1969 meeting of the Evangelical Theological Society, Henry took on serious distortions of the Reformation teaching regarding justification. The doctrinal truth that sinners are justified sola fide, by faith alone, had been twisted by “Neo-Protestants” into what Henry identified as “a perverse speculative theory of epistemological justification by skepticism (179).” As he explains, some theologians had twisted “justification by faith” to mean a rejection of divinely revealed truth, the historical reliability of salvation history, and the miracles recorded in the Bible as actual events which occurred in actual space and time.

Henry aimed his critiques at theologians of the Neo-Orthodox movement including Karl Barth, Rudolph Bultman, Paul Tillich, and others. He demonstrated that these “Neo-Protestants” misrepresented justification by faith, using it as an excuse to jettison the very content and historical events that are foundational to the Christian faith (180). He concluded, “The mind of modern man, whose doubt and sense of meaninglessness even theologians venture to justify, stumbles in blindness and night. May God who justifies authentically, on his own terms, and in his own way, cause the Light to shine and the Word to be heard again (194).”

“Basics of the Faith”

The second book under consideration here is Carl F.H. Henry’s Basics of the Faith: an Evangelical Introduction to Christian Doctrine. As Kevin J. Vanhoozer explains in the introduction, the chapters of this book originated as a series of articles edited by Henry for Christianity Today from 1961-1962 (1-2). Henry commissioned a group of expert scholars and theologians from a variety of denominations to address various theological topics ranging from revelation to Scripture, to the work of Christ, and so on. The volume functions as both a concise systematic theology and a snapshot of evangelicalism’s concerns in the mid-20th Century.

Apologetics junkies will be interested to learn that Cornelius Van Til contributed the chapter on “Original Sin, Imputation, and Inability” (144-152). Van Til traces theological claims about the nature of sin and man’s inability, contrasting Socrates and the Apostle Paul’s search for definitions of the good, the true, and the beautiful. While Socrates began and ended with man, Paul’s encounter with the living Christ set him on a different path (145). Through the imputation of Christ’s righteousness, Paul also recognized the imputation of Adam’s sin on all of humanity (cf. Romans 5:19). Van Til succinctly lays out the Bible’s teaching on original sin, imputed sin, and man’s consequent inability to merit favor with God.

In what he terms “The Synthesis”, Van Til traces the various ways these doctrines have been diluted or outright distorted, beginning with the Pelagian heresy of each man as a new Adam with a clean slate (147-149). When arriving at Neo-Orthodox “modern theologians”, the author acknowledges their expressed desire to be “biblical and Christological” in their view of sin. The problem was that the “Christ” they claimed to believe in was himself a reinterpretation, conformed to their own insistence on autonomous reasoning (149). Van Til rightly concluded that unless our definition of sin originates with the Christ of the Bible, then “we have no intelligible foundation” for recognizing our naturally hostile relationship to God in the first place (151).

I was particularly excited to see a chapter dedicated to the doctrine of adoption (281-289). The author, J. Theodore Mueller (1855-1967) produced his own take on Christian Dogmatics in 1934 and was a well-regarded Lutheran theologian. Appropriately, his chapter on adoption follows H.D. McDonald’s chapter on Justification by Faith. Mueller presents adoption as an often neglected but comforting truth of the redeemed sinner’s new status as one graciously brought into the family of God. Adoption is about “believers, who by nature were alienated from God and were under his righteous judgement, are received by him as his dear children and heirs of eternal life (282).” Citing Ephesians 1:4 and Galatians 4:4-5, the author points out that “adoption is an act of God’s free grace and excludes all human merit; it is absolutely sola gratia (284).” Mueller concludes with a section on “The Application of the Doctrine”, which is really more of a brief historical survey than practical application (287-288).

Conclusion

Carl F.H. Henry is one of the great theologians of our time, pushing back against modernism’s claims that the Christian faith must be revised. Both Architect of Evangelicalism and Basics of the Faith are significant works, centering around the question of what it means to be an “evangelical.” In them, Henry has given us ample evidence that the best of the evangelical movement stands in the great tradition of orthodox Christianity, while also having much to say to the ultimate needs of modern man.

A copy of each book was provided by the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

Robert, thank you very much for the kind words, brother. That sincerely means a lot to me that your spirit…