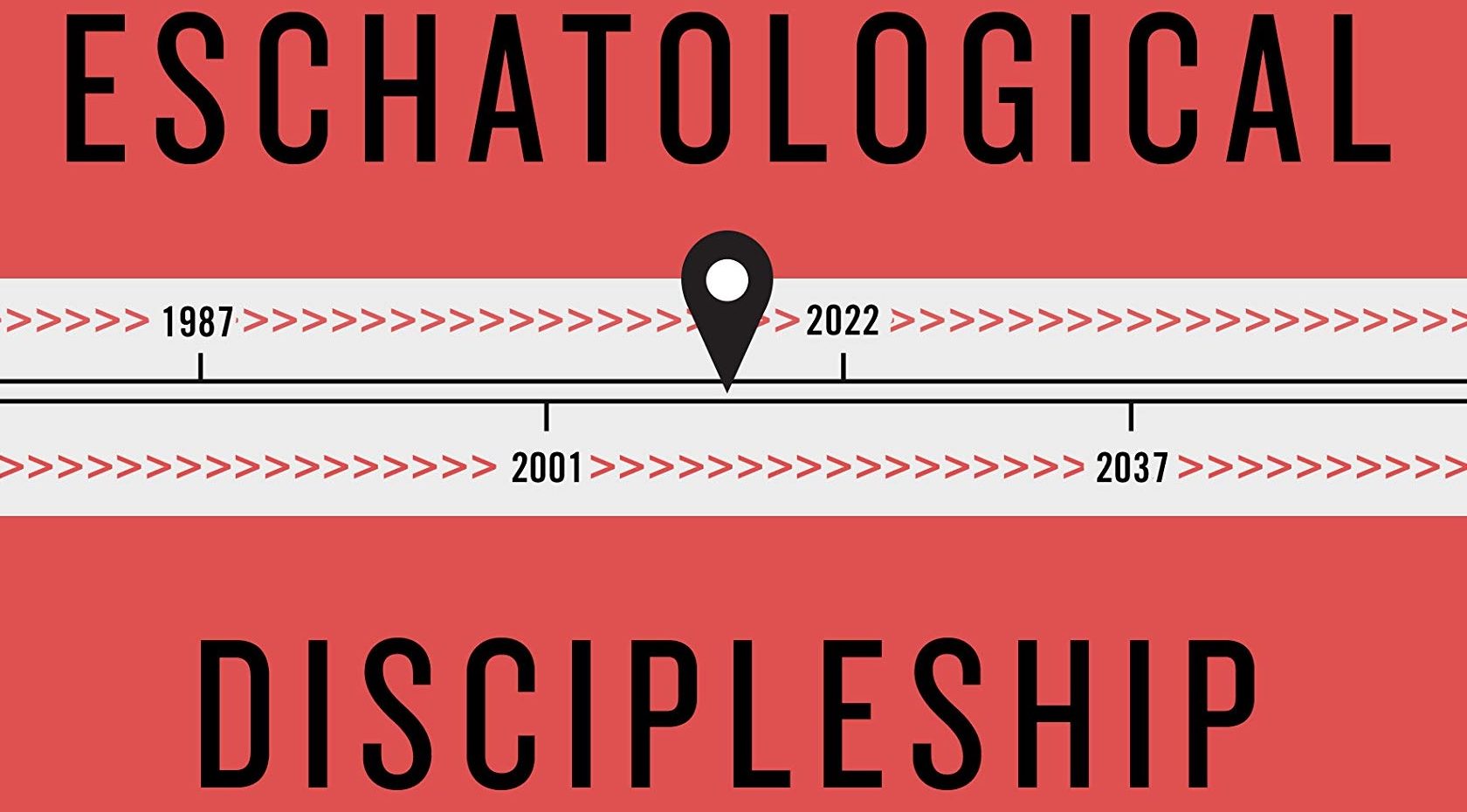

Eschatological Discipleship:

Leading Christians to Understand

Their Historical and Cultural Context

Review by Chuck Ivey

Wax, Trevin K., Eschatological Discipleship: Leading Christians to Understand Their Historical and Cultural Context. (Publisher: B&H Academic), 2018. 269 pp. $29.99

Biographical Sketch of the Author

Trevin Wax is the Bible and Reference Publisher for Lifeway. He served as director of Bible and Reference Publishing for Holman Publishing in the production of the Christian Standard Bible (CSB). His other books include This Is Our Time, Gospel Centered Teaching, and Holy Subversion. He regularly blogs at The Gospel Coalition.

Summary of the Contents

What is the right way to view the call of Christ in Matthew 28:19 to go and make disciples and not merely converts? What does discipleship actually look like in practice? We know that a disciple is literally a “learner,” but how is it different from just being a student? Trevin Wax offers some answers to these questions in Eschatological Discipleship.

In Part I, the author begins with “Defining Eschatological Discipleship”. Thankfully this has nothing to do with insanely detailed end times charts. You won’t learn the secret identity of the Antichrist here. By “eschatology”, Wax simply means what the word actually refers to, the study of last things. The question, “What time is it?” informs worldview. Wax argues that eschatology should inform and influence how we do discipleship. Where we are in the timeline of history will determine the right way to live out the Christian life.

Part II looks at the “Biblical Foundations for Eschatological Discipleship”. The Bible’s teaching on discipleship is broken down into Old Testament, the Gospels and Acts, and finally Paul’s letters. Wax argues that this concept is found throughout Scripture.

Part III, “Christianity in Light of Rival Eschatologies” then takes up the next four chapters. After a chapter introducing the idea of rival eschatologies, Christianity is compared and contrasted with the Enlightenment, the Sexual Revolution, and Consumerism. The author makes the case that understanding these competing “eschatologies” is vital for believers who want to “live on mission” consistently.

Part IV’s “Eschatological Discipleship for Evangelicalism” contains just one chapter on “Evangelical Conceptions of Discipleship”. Wax examines these conceptions under the categories of “Discipleship as Evangelistic Reproduction”, “Discipleship in Terms of Personal Piety”, and “Discipleship That is Gospel-Centered in Its Motivation”. He gives some strengths and weaknesses of each of these categories.

In the conclusion, Wax briefly restates his major points. Standard Bibliography and Scripture, Name, and Subject Indices are included.

Critical Evaluation

Too many of us as believers make the mistake of assuming the Christian life is either about thinking, feeling, or doing. Those of us who love to teach can easily pull up with our theological dump truck and unintentionally leave people buried under a pile of orthodox doctrines that don’t actually get put into practice. There is also the danger of just hanging out and “doing life” without ever dealing with the content of the faith once for all delivered to the saints (cf. Jude 3). There has to be both content or information being passed on and a relational aspect to discipleship. Discipleship is about more than just passing on information, but it is also more than just saying and doing nice things.

Wax argues for a holistic view of discipleship and helpfully unpacks what that looks like. Citing Greg Allison, he explains that a balanced view of discipleship involves orthodoxy, orthopraxy, and orthopatheia (7). Put another way, disciple-makers should pursue sound doctrine, right practice, and proper sentiment. Biblical discipleship is not about a onetime decisionism that checks off a box and puts the Christian life on a shelf. Discipleship affects all of life. This is consistent with the Puritan idea of having our heads, hearts, and hands submitted to Christ.

I appreciated the way that Wax explains “modeling” or “imitation” as discipleship goals (8-11). By modeling, he means that the disciple is encouraged to imitate the behavior and reasoning of the disciple-maker. This is one of the more helpful (and convicting) sections of the book. Imagine if all of us were able to say, “Follow me as I follow Christ.”, with a clear conscience.

In Part 3 Wax argues that competing worldviews which alter or deny the historic Christian faith are also rival eschatologies. They amount to “a confrontation between timelines, or calendars” and different “vision of history” than what Christians should recognize (96). Citing Oliver O’Donovan, he insightfully points out the difficulty of understanding our own time and worldview, by virtue of the fact that we are living in it now. As someone once put it, a fish would have a hard time describing wetness.

Yes, the dreaded issue of “social justice” comes up in this book. But Wax takes what I think is the right approach here, much like he does throughout this book. I appreciated the balanced tone Wax takes when he writes, “To reduce the Great Commission to evangelism or the Great Commandment to mere social involvement runs the risk of putting asunder what Jesus intended to stay together (56).” Anyone either looking for a hot take on white nationalism or Marxism (or for that matter, a defense of either one) is going to be disappointed by this book.

In the last chapter, Wax calls his readers to dig into further study with questions about what Scripture has to say about our place in God’s timeline (221). What does the wisdom literature have to say about the eschatological status of Israel? In what ways are New Testament ethics grounded in eschatology?

Wax also concludes by admitting there are some dangers in taking an eschatological perspective on discipleship. For example, a kind of relativism could set in where the believer starts to think that the answer to “What time is it?” can vary from culture to culture (222). This could make Christianity itself true for some but not for others. There is also the threat of syncretism or blending Christianity with other belief systems until it’s no longer true Christianity.

Conclusion

In Eschatological Discipleship, Trevin Wax gives Christians ample reason to commit or recommit to making disciples. He engages with many of the relevant passages of Scripture that address discipleship (cf. Matthew 28:16-20; Luke 24:44-49; Acts 1:6-9). Some of the rival worldviews to Christianity are handled thoughtfully and biblically. Plenty of readers will find areas of disagreement with Wax but this book is still a helpful resource and contribution to the study and practice of being a disciple-making disciple. Wax ends this book with an appropriate twist on Kuyper’s famous line about Christ’s claim of “Mine!” over every square inch of human existence. Jesus Christ is Lord over every area of creation, including time itself.

A copy of this book was provided by the publisher in exchange for an honest review.

Robert, thank you very much for the kind words, brother. That sincerely means a lot to me that your spirit…